Not knowing when a return trip would be possible, Asena Tahir, a Uyghur teenager and her family left their beloved homeland after months of worrying that her father would be sent to an internment camp. With the hope of setting foot in a free land, the family fled thousands of miles to their new home in the United States. Yet memories haunt; threats follow; old fears evolve into new concerns.

In 2017, the government of China began the mass incarceration of Uyghur people, one of the Turkic ethnic groups indigenous to the Xinjiang area in northwest China. The action was taken under the claim of countering “religious extremism,” although most detainees are just ordinary Muslims and commit no crimes.

The 17-year-old Tahir decided to take on the responsibility as a Uyghur, speaking up for her people. So did the others: a son, a mother, a granddaughter, and a grandson. Through one object, each of them tells a story about who they are - as a Uyghur.

A mother who owned an import-export company with her husband in Urumqi. A survivor who has experienced re-education camp in her homeland.

Zumrat Dawut came to the United States with her Pakistani husband and their three children to seek asylum in 2019. She has testified about her experience being in a “concentration camp” at a panel on the sidelines of United Nations General Assembly gathering in New York in September, 2019. According to Dawut, life back in her homeland was always in close surveillance.

“We were so happy on the day when my whole family got the U.S. visa. It was an unforgettable moment, so we ordered this at a store in Urumqi as a souvenir. I took this with me from Urumqi to Pakistan, and from Pakistan to America. Every time I see this, it reminds me of the happy moment,” said Dawut.

A Uyghur American. Founder of the East Turkistan National Awakening Movement. A grandson who was told by his grandfather not to call him anymore out of fear for detention.

Coming to the United States as an asylum seeker at the age of seven, he is now a U.S. citizen. He firmly believes that an independent nation is necessary for Uyghurs and other Turkic ethnic groups in the region.

“The first time I learned about the flag of East Turkistan was when I first arrived in the United States, in 2000 June 4th. My father was the first one who explained it to me that we used to have an independent country called East Turkistan, and this blue and white flag with the crescent moon is the flag of East Turkistan. I learned that hundreds of thousands of our ancestors gave their lives fighting for our independence. Since then I have dedicated my life to struggle for people, freedom and independence from Chinese occupation,” said Hudayar.

A Uyghur. An immigrant. A sister. A refugee. A person.

The paper she holds in her hand is a census form that was given to all residents in Xinjiang Uyghur Autonomous Region, China, in 2017. Tahir explains that the Chinese government grades the citizens based on the answers they provide. People who are Uyghur, practice Islam, pray frequently, and have travelled abroad will have points deducted and then be classified as dangerous.

The consequence: internment camps. Tahir’s father sensed a danger and decided to take his family to seek asylum in the United States. The paper represents “the change of our destiny,” said Tahir.

A person who is passionate about history. A son who hasn’t been able to contact his parents since 2017. An international student who had to quit school because of the financial cutoff.

Erkin has had the notebooks since he was in high school in his homeland.

He wrote down his thoughts about Uyghur society, business ideas, Uyghur identities, as well as Uyghur websites, which by now were all gone.

“It reminds me of my own history and the ‘good old days’,” he added, “relatively good comparing to now.” The notebook with three leaves on the cover is the one he got at the learning institution where he studied English during a summer in Urumqi. It was a popular school for Uyghurs, that have from 50 to 100 branches within the region. They were all shut down, according to Erkin. The founder, who was Uyghur, was believed to be sentenced 20 years in prison.

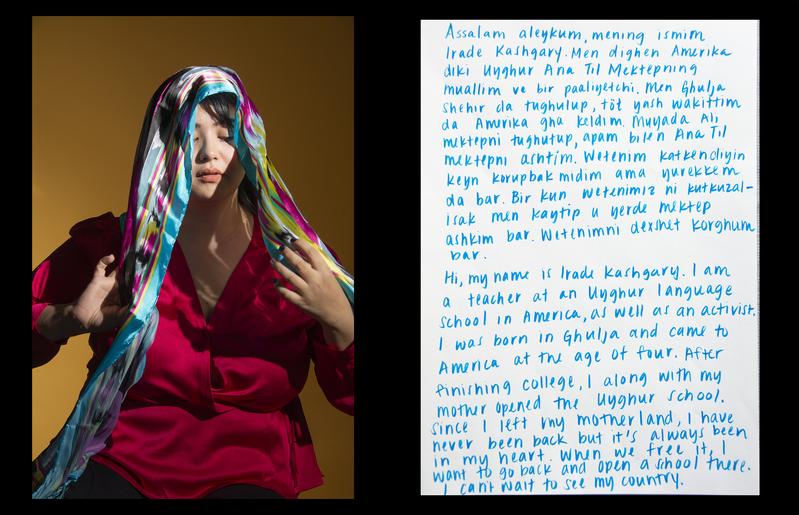

A Uyghur American. Co-founder of a heritage language and cultural school for Uyghur kids in northern Virginia. A granddaughter who cannot freely visit her grandparents in the Xinjiang area.

Irade Kashgary came to the United States at the age of four as an asylum seeker. For a period of time in her childhood and teenage years, she has once felt withdrawn about being a Uyghur due to the complicated political situations.

Now she teaches Uyghur culture and language to Uyghur American kids and teenagers at the Sunday school that she co-founded with her mother.

The Uyghur head scarf, etles yaghlik, brings her happy memories. The yaghlik is given out when the bride and groom first come in at a wedding. It is also put around guests’ necks as a sign of the hosts’ thankfulness for celebrating the moment together.

“I've been to many, many weddings in the diaspora community just because we get invited whenever someone within the community gets married. It's been a really strong part of me being able to keep my culture. I think because those weddings, even if, you know, I wasn't as engaged with the community in some parts of my life, would be a place for me to connect with them, see them,” said Kashgary.

She also explains that the majority of women in their homeland don’t wear hijab. “They just wear yaghlik kind of casually not to cover their hair but rather just to keep hair away from their faces. It’s really representative the way we practice Islam and especially right now when China is saying that we are terrorists and a lot of reeducation is happening to prevent terrorism. No, this is just one way to show that we are very colorful and peaceful culture, and I know it’s just a piece of cloth, but in a way, just the way women wear it day-to-day, it shows a lot on who we are,” said Kashgary.

(To read the Chinese version of this article, please click: 黃郁菁/命運不再沉默──離開新疆的維吾爾人,與他們手心上的故事)

深度求真 眾聲同行

獨立的精神,是自由思想的條件。獨立的媒體,才能守護公共領域,讓自由的討論和真相浮現。

在艱困的媒體環境,《報導者》堅持以非營利組織的模式投入公共領域的調查與深度報導。我們透過讀者的贊助支持來營運,不仰賴商業廣告置入,在獨立自主的前提下,穿梭在各項重要公共議題中。

今年是《報導者》成立十週年,請支持我們持續追蹤國內外新聞事件的真相,度過下一個十年的挑戰。