“No more arresting emblems of the modern culture of nationalism exist than cenotaphs and tombs of Unknown Soldiers. The public ceremonial reverence accorded these monuments precisely because they are either deliberately empty or no one knows who lies inside them … Yet void as these tombs are of identifiable mortal remains or immortal souls, they are nonetheless saturated with ghostly national imaginings.”Benedict Anderson, Imagined Communities: Reflections on the Origin and Spread of Nationalism, p.9

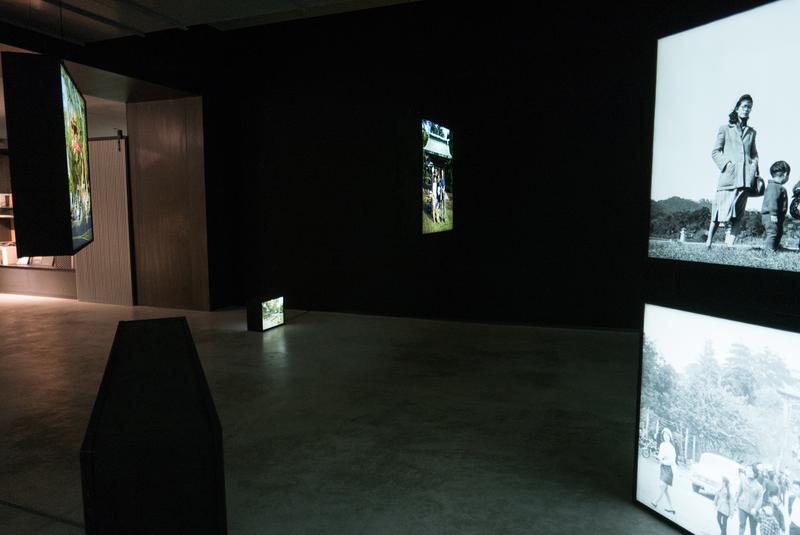

How can we understand the shifting changes of the Taiwanese identity? What methods do artists use that let us reflect upon the changes in our own identities? In 2018, Liang-Pin Tsao (曹良賓) opened an exhibition at TKG+ Projects examining “identity” and encounters with “history”. When entering the exhibition hall, it’s as though we had entered the shadow of history, gazing upon the countless scattered images of the Martyrs’ Shrine (忠烈祠) suspended in mid-air, as the faint light casts down onto the audience below. This dimly lit and shifting exhibition space allows us to pause and consider those questions of historical origin and identity, such as, “how does one become Taiwanese?”

Becoming / Taiwanese (《想像之所》) and Tsao’s previous work, SOJOURN (《中途》), are completely different. The images in SOJOURN were taken during the artist’s study and road trips in America. These images maintain a frigid aesthetics. In contrast, Becoming / Taiwanese more so examines identity and the fabric of history. If we say that the “non-places” of SOJOURN refer to an individual’s homelessness and aimless wandering, then Becoming / Taiwanese turns to look at the historically and culturally rich “Martyrs’ Shrine” (忠烈祠). Though the two have their differences, both present a certain aloofness to their alienation. Something important to note is that while Becoming / Taiwanese attempts to navigate the core foundation of the Taiwanese people, like SOJOURN, it seems unable to find its own anchor.

How do we address the existence of the Martyrs’ Shrine today? Is it a colonial legacy that preserves our imaginings of the nation through the sacrifice and worship of martyrs? Similarly, in facing a national system that demands sacrifice as though it were a religion, how can we reevaluate this period in our history? Compared to the solemn dignity of the Martyrs’ Shrine that served as a sanctuary for the nation’s martyrs during its early construction, many people today have long since transformed the Martyrs’ Shrine from a sacred symbol to one of ‘secularisation’.

From the images of Martyrs’ Shrines taken by Liang-Pin Tsao all over Taiwan, roughly all of them can be perceived as manifestations of this “secularisation”. Few people today are aware of the Martyrs’ Shrine’s “symbolic meaning as one that strictly enforces and moulds our national imagination”. More often, people are appropriating the exotic symbol of Japaneseness or Chineseness that the Martyr’s Shrines embody. Many people go there for wedding shoots, to cosplay, play mobile games, walk the dog, or just treat it as a recreational area in a park. On a serious note, how ought we best understand the “blasphemous” behavior performed there, in which our nation’s martyrs are dismissed?

First of all, perhaps we must first turn our attention back to the Martyrs’ Shrine itself. The Martyrs’ Shrine occupies one of the major roles in the operation of the state. It is also the site where the “imagined community” of a nation’s peoples is formed. According to philosopher Karatani Kojin (柄谷行人), only when the people are made to associate sacrifice for their country with eternal life can one say a nation has truly been formed. He also maintains that in addition to religion, such ideas of life and death can also be legitimized through the imaginary mechanisms of literature and aesthetics.

That is to say, the state mechanism will continually reproduce the narrative of martyrdom in order to consolidate the idea of the nation. In reality, during his adolescent years of compulsory education, Liang-Pin Tsao was also “enraptured” by this historical narrative of heroic sacrifice for one’s country.

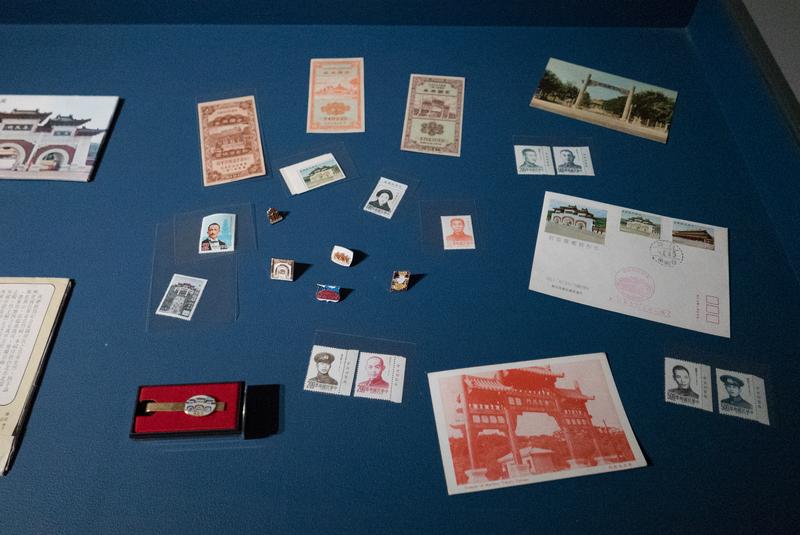

However, rather than calling Becoming / Taiwanese a representation of the artist’s complicated emotions towards national sentiment, it would be better to say, in this era of transitional justice, it casts doubt on the “imagined community” of the nation we putatively shared. Consequently, in the ‘Document Section’ of the exhibition, we can see the many struggles and contrasts between Taiwan-centered or party-state historiography, allowing viewers to become aware of the various problems in these historical narratives: the formation of authority figures, the dominance of Han-Chinese centered perspective, bias, oversimplification, appraisal and censuring, as well as the lack of the people’s neutered voice, to name a few.

So how are we to face this previously fabricated history, despite it once evoking genuine emotion? I believe, rather than just passively accepting this grand historical narrative, we could instead actively write and shape our own history. Becoming / Taiwanese is a construction and revisitation of history, allowing us to question established historical narratives.

Returning our attention to the issue of photography, Becoming / Taiwanese is igneous in its physical use of the exhibition space. Liang-Pin Tsao uses “double-sided lightboxes” to present his images within the exhibition, each box varying in size and randomly scattered about the exhibition hall, forcing viewers to engage with these images through natural movement.

In another respect, these double-sided lightboxes also present an implied “contrast of past and present”. The front side presents the current state of the Martyrs’ Shrine as photographed by the artist; the back side reflects relevant images of the original Martyrs’ Shrine, dug up from old photos. While the majority of these old black-and-white photos were taken by anonymous photographers, they are also interspersed with works of historically famous Taiwanese photographers, such as Chang Tsai (張才) and Lin Shou-yi (林壽鎰). Viewers may notice that he has used these images of ordinary people to echo the locations and content taken in his own photos.

Furthermore, Becoming / Taiwanese distinguishes itself from the “traditional photography exhibit”, wherein works are framed and mounted on walls in an orderly fashion, each piece flaunting the excellence of their artist. By breaking away from the confines of the “traditional photography exhibit”, one could say it transforms these works into an overall atmosphere of “installation” or “space”. This isn’t just an emphasis on the works themselves, but more importantly, it allows us to revisit the historical records of Taiwan.

Though the construction of this space is awe-inspiring, people tend to associate it with the exhibitory conventions in modern art, so it’s harder to inspire viewers to reflect on the past. In addition, it would be impossible for him to avoid the ethical problems in photographing his subject matter. The ethical problem concerns his aestheticization of the individuals and groups of people relaxing and sightseeing at the Martyrs’ Shrine. In other words, if visitors to the Martyrs’ Shrine are said to consume the site’s exotic atmosphere, is the artist not also consuming the images of the visitors?

From another perspective, those people that appear to taint the sanctity of the Martyrs’ Shrine are actually reconstructing the image associated with the shrine. Regardless of whether it’s using the Japanese symbols of the Martyrs’ Shrine, or using the shrine’s facilities as a space for relaxation and recreation, the actions of these people provide an opportunity to break away from the heavy historical burdens we carry. By perceiving this memorial space with such nonchalance, a vitality is injected into the scene, it is no longer simply a space of perpetual mourning.

So, should we embrace this modern-day individual’s consumption and enjoyment of the shrine, and abandon the construction of the national image? The currently living, whose short lives are temporary, alongside the immortal dead, who have already departed, create a fascinating contrast. Personally speaking, it is the contradictions of the Martyrs’ Shrine that are most intriguing. Perhaps the Martyrs’ Shrine should not be banned as a space of recreation for the living, nor should it completely shed its sanctity and historical significance. Perhaps it is more important that the two co-exist.

According to French philosopher Georges Bataille, “taboo” and “transgression” have a mutually dependent dialectical relationship. Without taboo, we wouldn’t be able to experience the pleasure and anxiety brought about when the lines of taboo are crossed. In other words, if we treat the Martyrs’ Shrine as a symbol of the sacred or taboo, then the “people’s transgressions” towards such a sacred place would be seen as a challenge. They need the Martyrs’ Shrine as a taboo symbol precisely so they can desecrate it. However, if the shrine has already completely shed its status as a national symbol, then there would be no boundary to cross. In other words, the tense relationship between “taboo” and “transgression” must always be maintained, and the rift that drives between them. There cannot be either “taboo” (the Shrine as a sacred symbol that cannot be transgressed) or “transgression” (the individual’s consumption of the shrine).

Something worth keeping in mind, it is difficult for the Martyrs’ Shrine to be either completely secular or sacred. It’s much more important that the two sides maintain a strictly dialectical relationship. In reality, Liang-Pin Tsao is the same as these recreational visitors to some degree, constantly transgressing against the ideological taboos of the Martyrs’ Shrine.

But the major difference between the artist and the recreational visitors lies in his firm awareness of “taboo”, affording him the strength to defy these set boundaries, and to challenge the accepted norms of the shrine through his works. In comparison, cosplayers, as consumers of the shrine, similarly capture the cultural symbolism of the Martyrs’ Shrine. However, being less aware of the “taboo” function of the Shrine, they tend to treat it as a site of entertainment. In other words, the greater the awareness of the issues of taboo, the greater the backlash for crossing these boundaries. In the same line of thinking, should viewers feel the strong historical shackles that bind them to the shrine, then there is greater motivation for wanting to transcend such history, deepening the impact of Becoming / Taiwanese. Inversely, should viewers solely engage with the exhibition’s aesthetics, then the significance of crossing such boundaries is lost. Perhaps it can be explained why the significance of Tsao’s works affects traditionally state-educated individuals differently to youth who have no clear knowledge of the shrine’s history. The former would understand this sense of “taboo and restriction”, while the latter would fail to understand what the exhibition aims to radically “transgress”, given that anything can be done in the Shrine these days.

So, how should we envision the “Taiwanese people”? Becoming / Taiwanese doesn’t give us an answer, but it more so requests viewers to transgress their preconceived notions of what a Taiwanese may be, constructing a potential Taiwanese subjectivity that is fluid, evolving, and has yet to be defined (this is precisely the kind of possibility that the English title of Becoming / Taiwanese refers to). According to nationalism scholar Benedict Anderson, rather than being dedicated to idols or individuals, martyr shrines and memorials materialize our imagination of a nation. Regardless of whether these memorials contain nothing more than people’s names, they are a concentration of the national consciousness, evoking images and feelings of “nation” within the people. Even if “nation” is an invented concept, it is not purely “fabricated” or “fictitious”, but more so “imagined” and “constructed”. Even an “imagined nation” still possesses the genuine emotions that we have invested in it. However, this does not mean that we have to approve of the national history constructed by the state, that is, an official nationalism (官方民族主義) enforced by the state from the top down. More important is a self-generating nationalism created from the bottom up (consisting of varying and diverse values), and Becoming / Taiwanese invites us to both challenge existing nationalism narratives and take the initiative in imagining other possibilities for Taiwan.

(To read the Chinese version of this article, please click: 沈柏逸/想像之所──我們怎麼「成為」台灣人?)

深度求真 眾聲同行

獨立的精神,是自由思想的條件。獨立的媒體,才能守護公共領域,讓自由的討論和真相浮現。

在艱困的媒體環境,《報導者》堅持以非營利組織的模式投入公共領域的調查與深度報導。我們透過讀者的贊助支持來營運,不仰賴商業廣告置入,在獨立自主的前提下,穿梭在各項重要公共議題中。

今年是《報導者》成立十週年,請支持我們持續追蹤國內外新聞事件的真相,度過下一個十年的挑戰。