I turned one year old just as martial law was lifted in Taiwan in 1987. But according to our esoteric calendar system, it was the 76th year of the Republic of China. I've hated numbers since I was a kid. Later I came to think it was because I was always juggling two different calendar systems around in my head. In any case, if memory is a product of personal experience, I obviously don't have any memories of the martial law period.

Seeing others reflect on this conservative era makes me think of how I reflect on my own childhood. Now that martial law is in the past, people talk enthusiastically about their experiences. They speak as boisterous and naive children who defeated the authorities with their wits alone. In these stories, the bad kids are always more interesting than the good kids, and it was better to break the rules than follow them. As for my own past, I can only say that there were no such pleasant surprises. For me, everything just seemed a little confusing without a real reason, a confusion that I suppressed.

I entered high school in 2001, a year after Taiwan experienced its first change of power between political parties. On my first day of high school, a high school senior gave us snacks to welcome us. As soon as she saw the course schedule on our classroom door, and who was on deck to teach us next, she jumped and excitedly yelled “it’s the Goddess of Ideology!”

“The Goddess of Ideology” was a seasoned teacher who taught the Three Principles of the People course. Twice a week, she would walk towards our classroom with a firm grip on the textbook. She introduced the class by saying:

“Ladies and gentlemen, today I’ve come to discuss the Three Principles of the People. What are the Three Principles of the People? Simply put, the Three Principles of the People is the ideology that rescued our nation. What is ideology? Ideology is a kind of thought, a kind of belief, and a kind of strength.”

Having taught for so many years, she spoke eloquently. She clearly knew the entire Three Principles text by heart. She spoke in volumes both casually and naturally without pausing; it was like wind and water. At the same time, her speeches were efficient, and didn't contain a single superfluous word. We couldn’t say whether this style of teaching was terse or beautiful.

The Goddess had an innovative method of teaching. Her trademark was to strictly dictate how we took notes. For example, we would write down this excerpt:

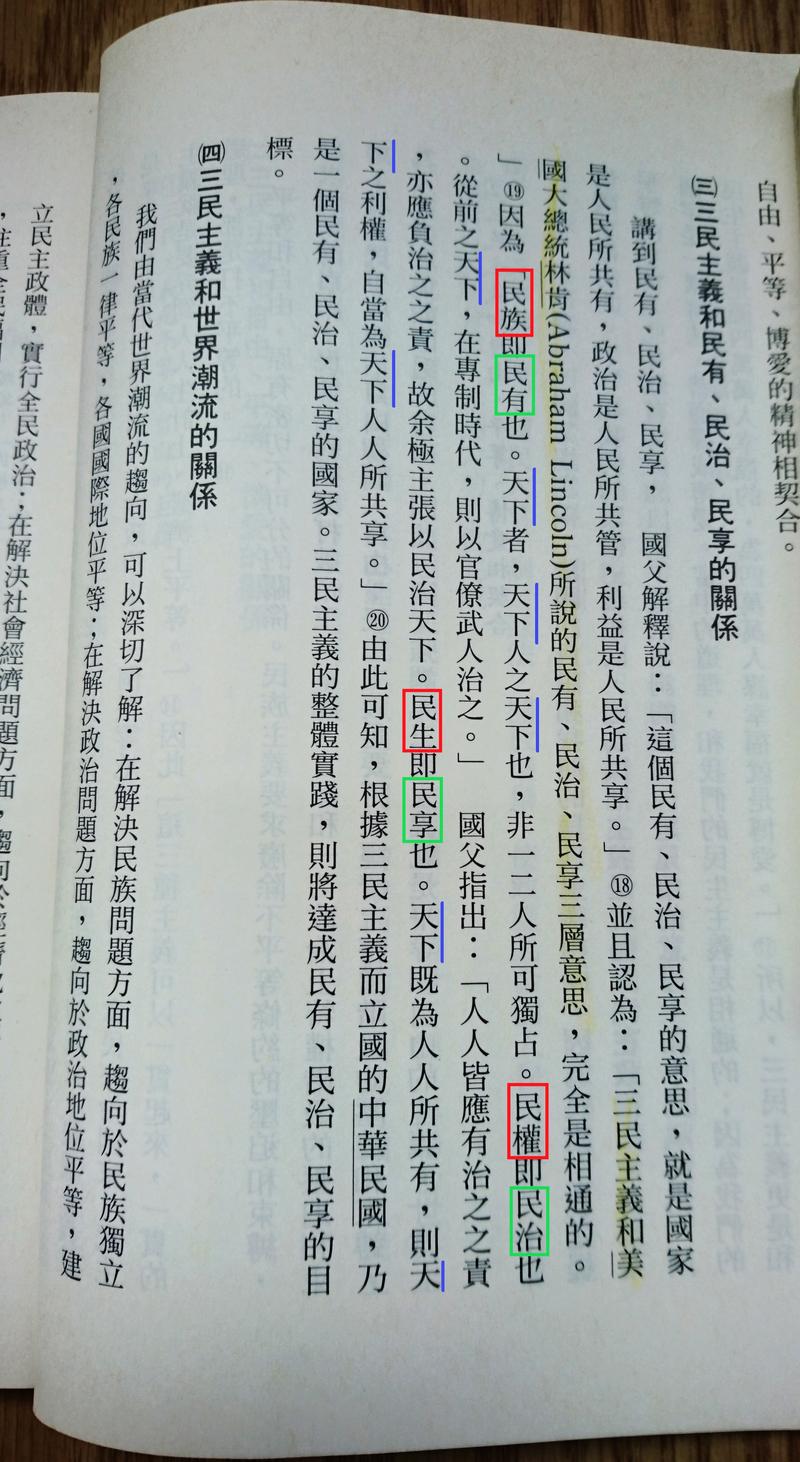

“Nationality is of the people. Those under heaven are under heaven, and that space cannot be monopolized by one or two people alone. Civil liberty is by the people. Before, in the autocratic era, everyone under heaven was governed by bureaucrats and warriors. Welfare is for the people. Since everything under heaven is commonly owned by the people, then all economic rights under heaven should naturally be shared by all people under heaven.”

The words “nationality”, “democracy” and “welfare” had to be boxed using a red pen; “of the people”, “by the people” and “for the people” were to be circled with a green pen. Every instance of “under heaven” must be underlined in blue ink, without exception. She slowly articulated all required annotations to the textbook so that we could transcribe them word-for-word without error. At the end of every semester she would collect all the textbooks from the class and inspect our notes to see if they conformed to each of her meticulous directives. She took care to repeat any main point three times. “The twentieth century must be, must be, must be the era of great welfare for the people.”

We all embraced the Goddess of Ideology. I had many good teachers during my high school years , but she was the most specialized of them all. In my first semester I was bewildered by her byzantine notation scheme and tried to learn about the Three Principles in my own way, but in the end, I always did poorly on the monthly quizzes.

For example, the following question appeared on the college entrance examination in 1998.

Of the four Western scholars’ views of equality seen below, which is the closest to Mr. Sun Yat-sen’s concept of “real equality” and “essential equality”? 1. Montesquieu thought that anything that is not forbidden by the law are rights that all people hold. This is “real equality.” 2. Rousseau thought that freedom and equality are inherent rights of humanity, and therefore to give up freedom and equality is to give up being a person, and furthermore to give up the rights and duties associated with being a person. 3. Rawls advocated the fundamental right of equality for all, and that all positions should be open to everyone with equal opportunity, and furthermore that the greatest care must be afforded to those who are at the greatest disadvantage in society. 4. Marx emphasized that the only way to establish an equal society is to completely abolish private property.

I was annoyed by this exam question, as if gnats were gnawing away at me. Saying it out loud, the differences seemed too trivial to even worth mention, but I would often obsess over the details of such a question. For example, the prompt would call Sun Yat-sen by “mister” but not Montesquieu, Rousseau, Rawls, or Marx... weren't they “misters” as well?

I still can’t forget the shock of seeing the following question on the monthly exam.

The Three Principles of the People, put simply, are: 1. The principles of nationality, democracy, and welfare. 2. An ideology to save the nation. 3. An ideology of equality and freedom. 4. An ideology of the people, by the people and for the people.

I remember thinking, “nationality, democracy, and welfare” are already simple enough, aren't they? But “saving the nation” is even simpler! It wasn’t until I looked back through the readings that I realized, the Goddess of Ideology had long ago read to us: “... by the simplest definition, the Three Principles are an ideology to save the nation,” repeating the phrases “simplest” and “save the nation” three times.

By the second semester, I had no more doubts. I finally understood how this course was different from the others: in the Three Principles course, there was no need to ask questions. I only needed to pay attention in class and follow the notes from the Goddess, and the class would be easy. From then on, like most other students, the subject of the Three Principles never confused me again.

In 2004, (or the 93rd year of the Republic), I graduated from high school. Just one year later, the Ministry of Education announced they would remove the Three Principles class from the high school curriculum, and combine the “civics” and “modern society” classes into a single course. In other words, the Three Principles of the People course was now history.

After that, the Goddess taught the new “civics and society” course. I’m not sure if students now call her the “Goddess of Civics and Society” but I’m sure she’s still a specialized and competent teacher. I’ve completely forgotten everything about the Three Principles, but that’s not really her problem.

I still think about that Three Principles class, and how a crucial point was clearly marked in red pen, and how confusion was easily settled through a test score. I think about the simplicity and clarity of the subject, how everyone moved together in unison, and that atmosphere of absolute focus. In reality, nostalgia for a bygone era is often the same thing as conservative ideology itself. If I am a posthumous child of the martial law period, then the Three Principles course I experienced was its living fossil. I can touch its rigidity, experience its mechanical repetition, and understand how the party-state education wasted the potential of its citizens. I don’t feel an ounce of pity.

When I turn through my memories today, what frightens me most is that in that entire year, the Goddess didn’t say anything to us other than the contents of the Three Principles. It encompassed the entirety of her life’s work. That’s how the martial law era was: my parents and their families were just as innocent, single-minded, and upward-striving. They were like her students, transcribing when it’s time to transcribe, forgetting when it’s time to forget. Every era has that class representative or model student: they understand the rules, observe the rules, and do their duty. They do everything earnestly and live an absent-minded life.

(To read the Chinese version of this article, please click:【戒嚴生活記憶】湯舒雯/主義女神 )

深度求真 眾聲同行

獨立的精神,是自由思想的條件。獨立的媒體,才能守護公共領域,讓自由的討論和真相浮現。

在艱困的媒體環境,《報導者》堅持以非營利組織的模式投入公共領域的調查與深度報導。我們透過讀者的贊助支持來營運,不仰賴商業廣告置入,在獨立自主的前提下,穿梭在各項重要公共議題中。

今年是《報導者》成立十週年,請支持我們持續追蹤國內外新聞事件的真相,度過下一個十年的挑戰。