In April 1989, budding photo-journalist Hsieh San-tai was sent to Beijing to cover high-level political meetings and sporting events. His visit coincided with the largest student protest in China's recent history, an event he captured for nearly forty days. But Hsieh's photos never made it into newspaper pages, and he left Beijing full of regret at his unfinished assignment.

30 years later, he's dusted off his photos, and compiled them into a new photobook — Howling 1989, printed by Yun Chen Publishing House. The following text and photos come from the book's preface, and are used with the publisher's permission.

On April 17, 1989, I arrived in Beijing from Hong Kong, and drove directly from the airport to Tiananmen Square. I witnessed the blood and tears of China's struggle for democracy, and left an assignment unfinished for 30 years.

I was one of the first Taiwanese reporters approved by the Chinese authorities to report in the country, and I was both excited and nervous about the trip.

That April, Taiwan was in shock over the death of Cheng Nan-jung (鄭南榕), a democracy activist who set himself on fire in protest of the ruling Chinese Nationalist Party's (KMT) clamp down on freedom of speech. Cheng's self-immolation, as well as the death of a good friend, were still fresh in my mind when the Independence Evening News (自立晚報) assigned me to go to Beijing to shoot some events and interviews. I didn't want to leave Taiwan, but I didn't want to give up this rare opportunity.

I had three assignments: One, cover the Asia Youth Gymnastics Championship. Two, cover the Asian Development Bank’s annual meeting. And three, cover Mikhail Gorbachev's state visit to China. At the time, all three were big events. Taiwan's Finance Minister, Shirley Kuo (郭婉容), was one of the first Taiwanese ministers to lead a delegation to attend a meeting in China, and Mikhail Gorbachev's state visit was the first formal meeting between China and Russia since the Sino-Soviet Split in 1956.

Before departing, I learned that Hu Yaobang (胡耀邦), the former general secretary of the Communist Party of China (CCP), had passed away, and grief-stricken students in Beijing were holding a spontaneous vigil in Tiananmen Square. When the plane landed, I didn't even stop by the hotel to drop off my luggage, I immediately made my way to Tiananmen Square to get some of my first shots, and send them back to Taiwan.

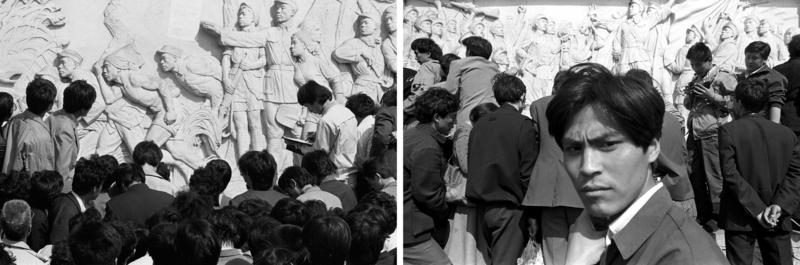

The atmosphere in the Square was still peaceful, and students were placing wreaths and funerary scrolls around the Monument to the People's Heroes. They praised Hu Yaobang as a political reformer, and demanded the CCP begin the process of democratization.

This was before the internet and digitization, so I took some simple darkroom equipment with me, more than a hundred roles of black and white and colour film, three kinds of slide negatives, and most importantly, a special roller photo fax machine developed by the Associated Press (AP). I had to wash the film myself, print the photos, and then send them back to Taiwan through the fax machine. The washroom in my hotel room became my dark room. It was 5x7 size photo film, and it took at least seven minutes to fax a single monochrome photo. If for any reason the scan was interrupted, you had to start all over from the beginning.

Spending so much time sending photos back to Taiwan raised suspicions, especially when I stayed at state-run hotels. I'd often get a knock on the door asking "Mr Hsieh, what are you doing" right in the middle of a fax. I had no choice but to take the machine to other hotels and beg to use their line. All this hard work is now unimaginable in the era of digital cameras and mobile phones.

When I wasn't on assignment, I spent all my time in Tiananmen Square.

It wasn't until April 19th that I felt nervous about the protest, when thousands of students gathered in front of the Xinhua Gate leading to Zhongnanhai — the central headquarters and residences of the CCP's top leadership. The CCP sent armed police units in response, and the first violent confrontations erupted.

At first, I wasn't afraid, I saw similar clashes between protesters and police in Taiwan. It was exciting to see the same spirit of democratization sprout up in China.

But trucking my camera equipment made me noticeable, and I'd often get questions like "where are you from?" I didn't want to raise too much suspicion, so I'd say "I'm a reporter from the south of China." That solicited some unusual responses like "you're an out-of-provincer!" (外省人), which left me dumbstruck on how to reply.

One time, a student from Xiamen University approached me and asked "do you speak the Minnan dialect?", a language spoken in Taiwan and the southern Chinese province of Fujian. So right there in Tiananmen Square, the two of us chatted care-free in a language totally unfamiliar to the locals in Beijing.

Chinese state newspapers didn't report on the student protests, there were only "outsiders" covering the situation in the square. One reporter from Reuters would make discreet inquiries, and became the main source for what was happening with the students.

It wasn't until the Beijing Students' Autonomous Federation was established — an organization that acted as the chief decision-making body for the student protesters — that students began to engrave steel plates in the square, and print their own publications. But as students began organizing better, the authorities became more nervous, and sped up their plans to evict the students.

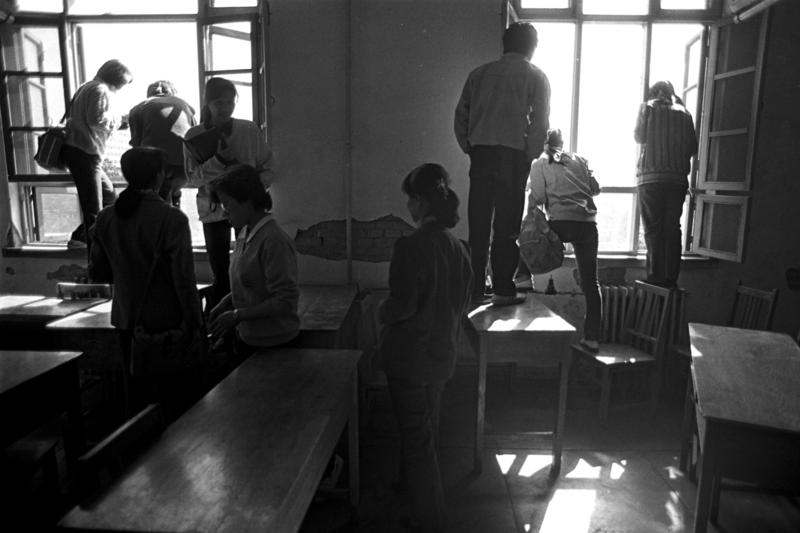

The April evenings in Beijing were chilly, and the students wrapped themselves in quilts, enduring hunger and the cold. Looking glum, they wrote big-characters on posters that read "We can tolerate hunger, but we can't tolerate a China without democracy!"

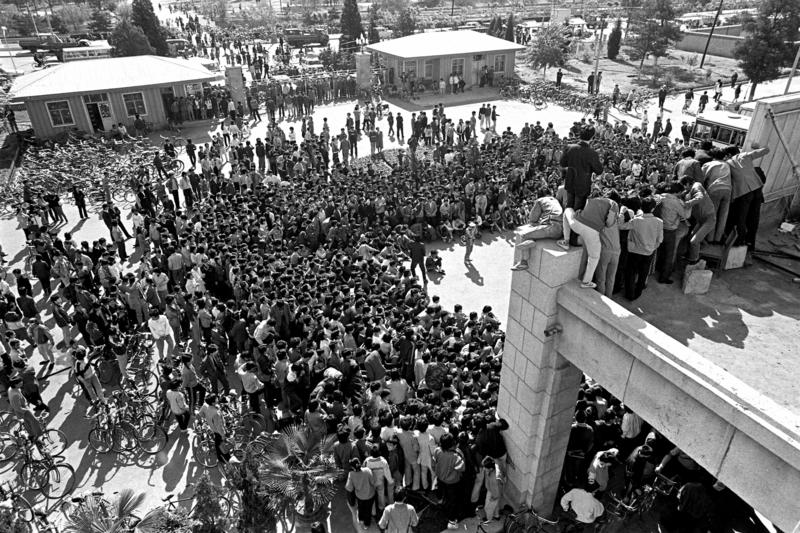

I tried to learn more about the students, so one of the protest leaders, Wang Dan (王丹), took me to Peking University to attend a student symposium and see his dormitory. There were six to eight students squeezed into bunk beds in Wang's dorm room. They lived frugally, but their hearts were full of lofty ideals.

Wang's parents were teachers, and I asked him how they felt about him taking part in the protests. "I spoke at length with my parents about this," he said. "They support our fight for democratic freedom in China." No one imagined that the protest would utterly change their lives.

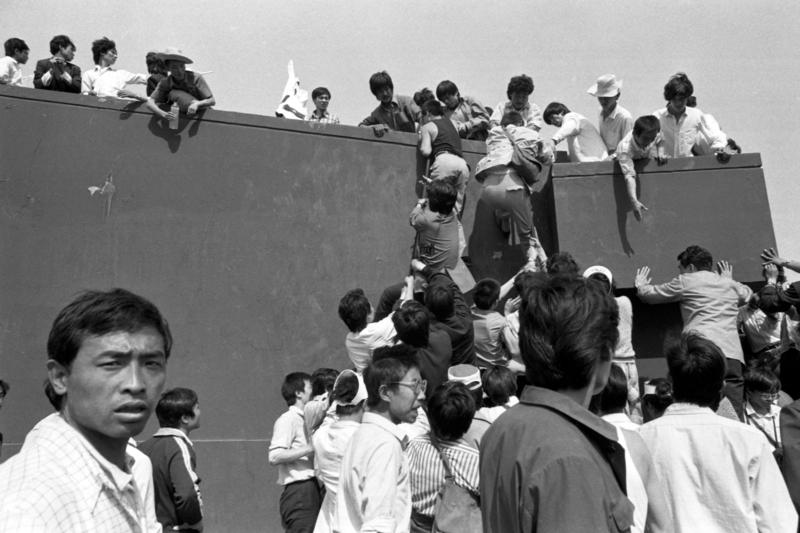

The students' hunger strike intensified by mid-May, and students were pouring in from all over China to take part in the protest. There were whispers that the PLA was outside the city and ready to use force to disperse the crowds. Everyone was jittery, and news agencies started worrying about the safety of their reporters. Holding a big camera in my hand, I was an obvious target.

My office also asked me to evacuate, and their calls only increased after martial law was announced on May 20. The control area around the square expanded, and violence broke out more frequently. People couldn't hide the fear and uncertainty in their eyes.

Eventually, the office cut off my compensation and forced me to return to Taipei. I told them in no uncertain terms that I was staying, but with only $100 US dollars and a return plane ticket in my pocket, I had no choice but to concede.

On May 23, three workers vandalized the Mao Zedong (毛澤東) portrait hanging on the Gate of Heavenly Peace, and I took my last photo.

I left Beijing the next day. I was filled with regret that I couldn't document the entire protest. I spent 40 days in Tiananmen Square.

Not long after I returned to Taipei, PLA units advanced on the students, and Tiananmen Square was stained with blood. Wang Dan and the student leaders were arrested, and many of the Chinese journalists I met were now missing.

My feelings were all over the place. I felt sad for the young students who sacrificed their lives for freedom and democracy, and I regret missing the opportunity to witness an important historical event. I also couldn't help but think that if I was still in the square, my situation would be very different right now.

Tiananmen Square was the only assignment I never finished. After returning to Taiwan, I clipped my resignation letter to my expense sheet, and quit my job at the Independence Evening Post for forcing me to come back. I hid these photos and regrets in a corner for nearly 30 years, that is, until Chang Chao-tang (張照堂) — a famous photographer and documentary filmmaker in Taiwan — saw the images.

"There's no need to feel regret, you were there, that's the most important thing," said Chang. "The process is important."

In the blink of an eye, 30 years have passed since June 4. Nowadays, when I look at those old images, I think of the students and their reckless abandon. "To the greatness of life, and to a glorious death!" That was a slogan on a poster at the time. I hope the images I shot can express even a fraction of their desire for democracy and freedom.

(To read the Chinese version of this article, please click: 塵封30年影像首度曝光:台灣記者在天安門廣場的40天)

Hsieh San-tai is a Taiwanese photo-journalist with experience at the Independence Evening Post (自立晚報), the Independence Morning Post (自立早報), the Taiwan Weekly (黑白新聞週刊), New Taiwan Weekly (新台灣週刊) and Power News (勁報). He's photographed a historic moments events in Taiwan, including the 1988 520 Peasant Movement, the 1987 National Assembly protests, and the country's first mayoral and presidential elections.

In recent years, his focus is on documenting Taiwan's vibrant civil society movements, including the labour movement, minority rights' movements, and the environmental protection movement.

深度求真 眾聲同行

獨立的精神,是自由思想的條件。獨立的媒體,才能守護公共領域,讓自由的討論和真相浮現。

在艱困的媒體環境,《報導者》堅持以非營利組織的模式投入公共領域的調查與深度報導。我們透過讀者的贊助支持來營運,不仰賴商業廣告置入,在獨立自主的前提下,穿梭在各項重要公共議題中。

今年是《報導者》成立十週年,請支持我們持續追蹤國內外新聞事件的真相,度過下一個十年的挑戰。